As a step toward creating equitable cultures at their institutions, many colleges and universities are developing land acknowledgements. In its simplest form, an Indigenous land acknowledgement is a formal statement by an organization recognizing that it sits on what was once the land of a Native American tribe. More comprehensively, a land acknowledgement provides an opportunity for a college or university to:

- foreground the marginalized history of the institution and its region;

- raise awareness about ongoing colonialism and land-based injustice;

- raise awareness about a lack of representation of Indigenous people; and

- formalize an action plan to support Indigenous people in the future.

According to the research paper Land Acknowledgement: A Trend in Higher Education and Nonprofit Organizations by Thomas E. Keefe, Associate Professor at Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design, acknowledging Indigenous lands and peoples has become common in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Almost all higher education institutions in Canada have what are sometimes called territorial acknowledgements.

In 2018, a movement began in the United States for colleges and universities to establish land acknowledgements. Additionally, many organizations other than colleges and universities — particularly cultural institutions — have developed indigenous land acknowledgements.

Guidelines for developing a land acknowledgement

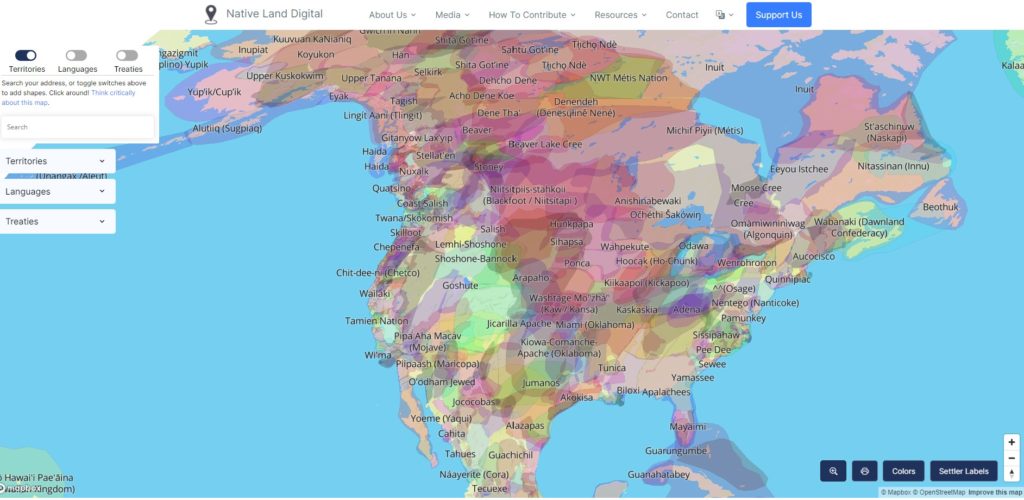

For a college or university wishing to establish an Indigenous land acknowledgement, the first step is to understand the Indigenous history of the land your institution currently sits on. For starters, the online tool Native Land Digital allows you to search for your location to find out what Indigenous groups have a history at your location.

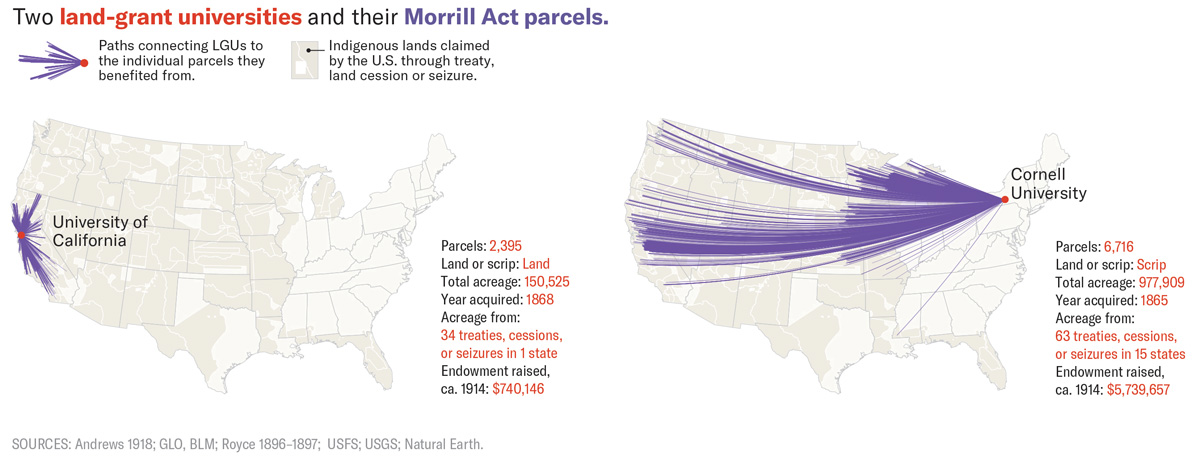

Another helpful resource is the extraordinary report Land-grab Universities by High Country News. It identifies the particular parcels of stolen land, often thousands of miles from campus, that seeded university endowments in land-grant institutions like University of Arkansas and University of Florida. In some cases land is still owned by universities or states and is generating rent and other income that support land-grant universities. The database built for that report is publicly searchable.

The land acknowledgement toolkit from the California Indian Culture and Sovereignty Center (CICSC) urges higher education institutions to follow a four-prong approach for land acknowledgements:

- Responsibility — Formally acknowledging the traditional stewards of the land and why the acknowledgement matters

- Reciprocity — How to build a process for acting in solidarity with Native Americans

- Respect — Understanding the history of colonialism and historical trauma

- Relationships — Building authentic relationships between Native American tribes and the institution

The guidelines the CICSC toolkit advises:

- Give land acknowledgements at events and activities held at campus, as well as the first day of class and on campus videos.

- Provide virtual land acknowledgements for faculty and students participating in virtual classrooms.

- How acknowledgement happens matters. It should not be formulaic and something staff “has to do,” but rather meaningful and mindful.

- Teach all staff and students the proper pronunciation of Native American tribal names.

The Native Governance Center offers two other detailed resources, A Guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgement and Beyond Land Acknowledgement. Their guidelines advise:

- Recognizing Native American tribes are here in the present and will be in the future. Do not relegate them to the past.

- Not asking an Indigenous person to present a welcome speech at a school event. Emotional labor adds undue stress to Indigenous people. And if you do ask an Indigenous person for their assistance in crafting the land acknowledgement, pay them for their work.

The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture has a guide to developing Indigenous land acknowledgements for cultural organizations with examples and resources.

Land acknowledgements include practical actions

Above all, the Native Governance Center forcefully argues, a land acknowledgement without an action plan amounts to little more than “optical allyship.” Other resources emphasize that land acknowledgements can devolve into meaningless box checking if they aren’t accompanied by practical plans that make a difference to Indigenous people.

“Our organization has received hundreds of inquiries from folks wanting help with their land acknowledgment statements,” the Beyond Land Acknowledgement guide explains. “Almost all of these inquiries have focused on land acknowledgment verbiage, rather than the all-important action steps for supporting Indigenous communities. Every moment spent agonizing over land acknowledgment wording is time that could be used to actually support Indigenous people.”

The action steps it suggests that colleges and universities can consider include building relationships, supporting protests, voluntary land taxes, land return initiatives, hiring programs, and tuition waiver policies.

University of Arkansas alumnus Summer Wilkie, writing in High Country News, also emphasizes building relationships and work to heal injustice. A tuition waiver for members of Indigenous communities will get little uptake if students don’t see themselves as welcome. She recommends required courses in Indigenous history, research programs that benefit Indigenous communities, and repatriating looted “artifacts” that university museum collections still benefit from.

“Land acknowledgments can range from perfunctory to profoundly moving,” Wilkie writes. “When they are poorly worded or produced in certain contexts, they can cause uncomfortable cognitive dissonance for Indigenous people . . . . I hope you can understand why Native American students might feel more irritated than honored when their classes begin with a compulsory land acknowledgment statement, or when they stumble across one on a website.”

Two good rules of thumb, as the above resources make clear, are to start the process of creating a land acknowledgement with humility and to view the written document as only an early step in an ongoing journey.

Equitable Language and Reframing: How We Think About Writing and Editing to Support Equity