Discourse in higher education often romanticizes the image of the cash-strapped college student scraping by on cheap pizza and ramen in crowded apartments with hand-me-down furniture. Many successful adults look back on their lean student years as a rite of passage.

But the romanticized image hides a genuine problem of students experiencing food insecurity that impairs learning and degree progress, and that disproportionately impacts poverty-affected and first-generation students.

Food insecurity can be defined as not having access to or the means of obtaining sufficient food to meet one’s basic needs. Food insecurity tends to be a private struggle and so goes unnoticed by or unrecognized at the institutional level and by individual faculty. Surveys of colleges and university students have shown:

- 41 percent of students experienced food insecurity within the prior month, according to the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice.

- of students who struggled with food insecurity, 69 percent considered dropping out of college, according to the Center for Community College Student Engagement.

- Black and Latino/a households experience food insecurity at a higher rate than white households (41 percent and 37 percent as compared to 23 percent), according to a study from the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University.

- of the 3.3 million students who were eligible for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), less than half participated, according to a 2018 Government Accountability Office study.

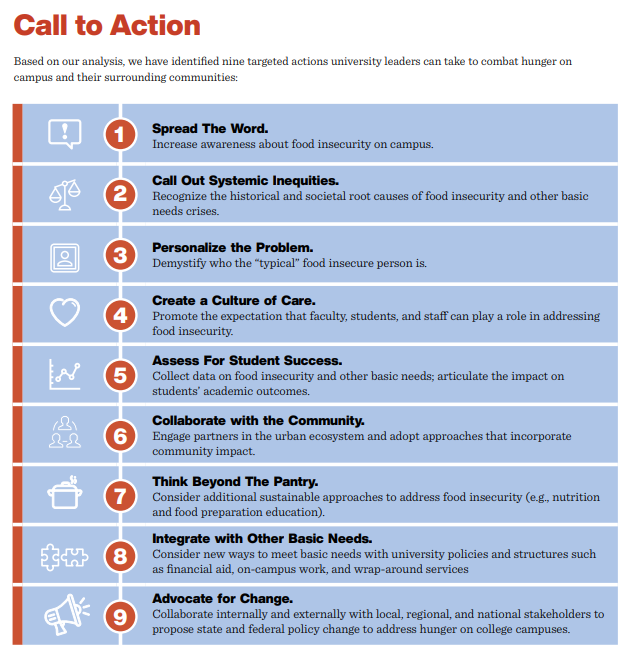

Food insecurity is a systemic problem that requires systemic attention, as an excellent report from the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities (APLU) and the Coalition of Urban Serving Universities makes clear. Some of the factors within higher education that influence the issue of food insecurity include policies and structures, awareness and accessibility, and inclusivity.

Food Insecurity at Urban Universities: Perspectives During the COVID-19 Pandemic, APLU and the Coalition of Urban Serving Universities

Nevertheless, there are practical steps that individual college faculty can take to reduce how food insecurity influences the learning progress of their students.

Listen well and refer effectively

For many students, food insecurity is not an isolated challenge but goes hand in hand with problems with housing, transportation, childcare, conflicts between work and study schedules, technology access, textbooks, and financial aid. In a recent article on academic disruption, Thomas Cavanagh, Vice Provost for Digital Learning at University of Central Florida, told Every Learner that the first signs of a student crisis are often first apparent in a technology problem the staff and faculty in his unit assist with.

“A student who has digital divide issues, oftentimes that’s not the only issue they have,” Cavanagh says. “They might have food insecurity or housing insecurity. Their financial aid is running out. Students would present to us first because they had a technical problem, but that wasn’t their only problem.”

As a result, he says, faculty and staff are often the first to refer students to the university’s support services. By understanding the interconnected nature of food insecurity, faculty can begin taking practical steps that have a positive impact on students.

Raise awareness

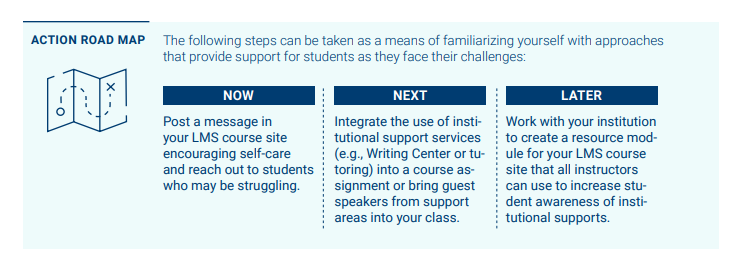

Faculty can use their classrooms to normalize getting support — not only for basic needs assistance but for health services or tutoring. Students may have the incorrect idea that “good students” must do everything independently. Faculty can send the message that getting help is a normal part of academic work. Practical ways to do this in the classroom include:

- Having visitors from the student services speak to the class directly.

- Referring frequently on the syllabus, in the LMS, and during class meetings to the services available on campus.

- Vary the ways students can engage with you — open office hours, videoconferencing, study group meetings — to build rapport and increase the chances they’ll share concerns with you.

Faculty can also encourage their departments to share information about food pantries, emergency funding, and other campus resources in departmental communications to students.

By destigmatizing support services, educators create a safer, more open attitude toward using these services.

Be prepared for the conversation

A good rapport with students may result in conversations about personal challenges that faculty feel they aren’t expert in. The University of Oregon Office of the Dean of Students created a useful resource with several ways to communicate with students about food insecurity. Some guiding principles for those conversations include:

- Listen with empathy

- Don’t blame

- Focus on providing information highlighting the benefits of support services

- Assure them they are entitled to support resources

Flexible and inclusive course design

All students — including those struggling with food insecurity — can benefit from flexible course design. This responsive approach allows students to shift between in-person and distance learning modalities if needed during a crisis or to keep an emerging challenge with work or family from becoming a crisis.

Flexible and multimodal approaches using digital learning move coursework closer to more accessible and equitable learning opportunities for students. Additionally, it allows for more empathetic teaching and humanizes online learning by engaging students and faculty in direct conversation, something not always possible in the traditional classroom.

The Caring for Students Playbook from Every Learner, the Online Learning Consortium, and Achieving the Dream recommends several instructional design and teaching practices that account for the challenges students may have. The goal of the recommendations is to ensure that individual courses don’t contribute to those challenges and widen equity gaps.

Advocate for institutional responses

As noted earlier, food insecurity among college students is a systemic problem with causes far beyond the direct influence of individual faculty. However, faculty can help address the problem by advocating for and supporting institutional responses.

An article from The Drexel University Center for Hunger-Free Communities outlines several possible institutional responses to food insecurity across four levels from basic response to lasting change:

- Emergency food: Design equitable and inclusive food pantries and meal-plan donation plans.

- Access to assistance programs and resources: Raise awareness and assist students in accessing public benefits programs, financial aid, and other non-emergency support.

- Community-based support: Sponsor or engage in local food systems, community gardens, community refrigerators, and student organizations.

- Economic justice: Advocate for affordable food and housing, living wages, and other policy changes.

In learning environments where up to 40 percent of students are experiencing food insecurity, a student-centered culture of care will inevitably need to confront that challenge. And institutions engaged broadly in reducing food insecurity for students in these ways are also creating more equitable, safer, accessible, and effective institutional cultures for their students overall.

Download Caring for Students Playbook: Six Recommendations