Even before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, Dr. Kristin Polizzotto and her colleagues at Kingsborough Community College (KBCC) in Brooklyn, New York, employed powerful online tools such as courseware from major publishers to engage students in biology online material outside the classroom.

But Polizzotto encountered a vexing problem. While students in her introductory biology class were highly motivated, and most planned careers in healthcare, many struggled with the online resources and underperformed on tests.

In addition to teaching the course material, Polizzotto says, “I try to help students construct the scaffolding for how scientists think and organize information. It’s a framework for all the new material they learn for the rest of their lives.”

That wasn’t showing up in the assessments, though, and Polizzotto suspected access to computer hardware and wifi — while an important factor — didn’t fully explain the problem. Her students were generally positive about their experience with the digital resources, but many complained about the exams and their perception of a disconnect between test questions and course learning objectives.

She eventually came to believe there were two significant barriers to her students’ success that she could influence: unfamiliar language on the exams and unaffordable course materials. Instead of an issue of readiness or effort on the students’ part, Polizzotto says, “I realized this was an equity issue.”

Over the following two years, Polizzotto and colleagues engaged in two major efforts to make the teaching and learning in introductory biology online at KBCC more equitable.

Revising tests and quizzes for language clarity

As described in a 2019 case study, Polizzotto began by taking a close look at the courseware test bank questions that students most often answered incorrectly.

“In some cases I was surprised because I thought they were easy questions,” she said. “When I asked the students about it, it became clear they misunderstood the questions due to the wording. I realized the questions were easy for me because I’m a native English speaker with a broad background in the sciences.”

Non-native English speakers are common at KBCC, which is part of the City University of New York system. Its student population of 15,000 includes many recent and first-generation immigrants. “Many speak Farsi, South Asian languages, or Russian,” Polizzotto says, “and there are quite a number of French Creole speakers from the Caribbean.”

Given the language challenges, many of Polizzotto’s students had an additional cognitive load during exams and quizzes to comprehend how questions were worded instead of the actual substance or content. “Sometimes,” she says, “the words being used were unnecessarily fancy, so to speak.”

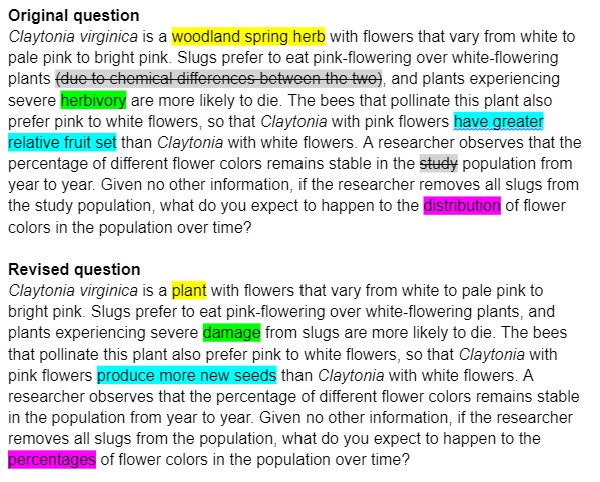

Below is a “before and after” comparison of a multiple-choice question from the test bank Campbell Biology, a commonly used text published by Pearson, with Polizzotto’s revision. Substituted words and phrases are highlighted, and deleted material is marked with a strikethrough.

“Prior to my revisions, some questions were tripping up between 75 percent and 90 percent of the students,” says Polizzotto. “After the revisions it was less than 25 percent. I was really surprised. It shows equity was what it’s been about all along.”

Building a better lab manual

After completing that project, Polizzotto and her colleagues examined students’ use of laboratory resources and found disparities there, as well.

To begin with, the lab manual was too expensive. “It cost $180,” she says. “Half of the students weren’t even buying it. When you’re doing in-person learning you can share with someone at the same table or check it out from the library. But with the switch to remote learning during the pandemic, those weren’t options.”

One solution was to seek out free Open Educational Resource (OER) manuals. But while Polizzotto found plenty of OER material on selected topics in biology (basic biochemistry, photosynthesis, cellular respiration, and genetics), there was much less on evolution, ecology, and organismal biology. So she and the KBCC biological sciences team set about writing a new lab manual.

“It had to be free, interactive, virtual, and asynchronous,” Polizzotto says.

She and her colleagues wrote the manual in the spring and summer of 2020 and then discussed it with students for feedback. “We’d see what wasn’t working very well, made edits, and got it ready to publish on online platforms in the spring of 2021. There are still errors that we try to fix now and then, but it’s had thousands of downloads around the world.”

The lab manual is available here and here, and Polizzotto and her colleagues published an article on the development of the lab manual in The Journal of Microbiology and Biology Education. They are now conducting an IRB-approved study with students to assess the impact of the OER lab manual.

Even after the return to full-time in-person teaching and learning, the new manual should be an invaluable tool for Polizzotto’s students. “Say a student misses a lab because their mother or grandmother had to go to the doctor and needed someone to translate for her,” she says.

“This happens all the time. Now they can have the lab experience and achieve the learning outcomes instead of just getting a zero. To me, that’s a step toward equity.”

Download Improving Critical Courses Using Digital Learning & Evidence-based Pedagogy