Cultural capital in higher education is a foundational concept of assets-based approaches to college and university education. It has indirectly informed the development of equity-centered learning, including practices like culturally relevant or culturally responsive pedagogy.

What is cultural capital?

Cultural capital is a form of social currency made up of the values, experiences, knowledge, and behaviors that assist a person in navigating culture. The concept is a way of characterizing non-economic or non-tangible resources that individuals draw on. Examples of cultural capital include dialect, credentials, and the social signaling of material items such as clothing.

The concept of cultural capital was first introduced by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in his 1973 paper, Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction, in which he asserted that the differences found in people’s cultural capital reinforced social class stratification. Bourdieu was interested in how cultural capital could be drawn on for social mobility across social class strata or how institutions — especially schools — could reinforce social class strata by passing on cultural capital. He identified three states in his cultural capital model:

- Embodied state: Knowledge an individual has.

- Objectified state: Material objects that carry social significance.

- Institutionalized state: Society’s measuring and ranking of cultural capital.

The three states in Bourdieu’s model work in tandem to comprise an individual’s cultural capital. In the 2005 article Whose Culture Has Capital?: A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth, Tara Yosso critiqued and expanded on the concept and presented her cultural wealth model, which has since informed discussions of assets-based pedagogy in colleges and universities.

Cultural capital in higher education

Discussions about applying the concept of cultural capital are more common in K-12 education and in Europe than they are in higher education in the U.S. The concept is potentially useful in higher education in at least two ways: to describe teaching practices and curricula that help students build cultural capital, and to describe teaching practices that enable students to draw on their existing cultural capital to support their success.

Both of those approaches can be seen in action in the report What Our Best College Instructors Do: Reflections By Students About Meaningful Learning Experiences. The report finds that students want to be recognized as individuals, want to be treated with respect and trust, and value connections between course content and “real life.” The voices in the report demonstrate many examples of faculty enabling students to draw on their cultural capital. For example, one student wrote:

“My best instructors work with their students, not only learning more but allowing the student to be vocal about where their education may not be inclusive to their needs in this area. This may also mean that the structure of school may clash with aspects of their cultural needs, such as important holidays and gatherings. This also extends to students’ abilities to do work within their own communities, such as being available for community work, religious practices, and even groundwork for systemic change they need, such as protests and advocating to local, state, and federal bodies. Flexibility in allowing students to explore important parts of their identities can be addressed by being open to discussion, moving away from western traditions in how students take in their lessons and how they show what they learn. This can also include students bringing up how they best learn, letting them relate the subject matter in the course to their experiences and also just allowing them time to deal with important aspects of their identities”

One example of curricular approaches that draw on students’ cultural capital is digital multimodal composition, which encourages students to use a broader range of language practices in lieu of traditional writing assignments. One literature review on digital multimodal composition practices found that it had benefits in social justice learning, expanded linguistic repertoire, and self-expression.

Racially and ethnically minoritized students and poverty-affected and first-generation students oftentimes have cultural capital that differs from dominant perspectives. The concept of cultural capital is often used to theorize and study lower participation in higher education among those student populations. For example, a 2017 study by Mads Meier Jæger and Stine Møllegaard from Social Science Research found that brief exposure to a student’s cultural capital created a biased perception of their academic ability in their instructors.

Implementing cultural capital in the college classroom

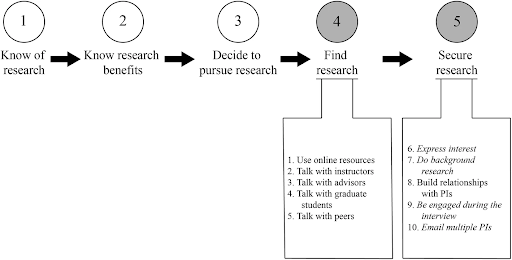

A third use of cultural capital is to theorize or describe barriers to academic progress when institutions privilege or require cultural knowledge that not all students will have. For example, a study proposing a model of undergraduate scientific research capital looks at the various barriers to students engaging in research activities necessary for successfully entering STEM careers. Economic capital — the ability to afford unpaid internships, for example — is a critical factor, as is social capital in the form of relationships and networks. But even accounting for those differences, tacit cultural knowledge about how to find and secure research opportunities is also important and “unevenly distributed to students,” the authors write.

From: Cultural capital in undergraduate research: an exploration of how biology students operationalize knowledge to access research experiences at a large, public research-intensive institution.

Discussions of cultural capital in education can tend toward deficits-based perspectives if students are described as having more or less cultural capital. An assets-based take on the concept frames students as having different kinds of cultural capital that colleges and universities are more or less successful at recognizing and drawing on.

Every student has reservoirs of experiences, knowledge, and skills that are potential strengths enabling academic success. Those strengths may include family support, peer groups, religious communities, and broad language practices. By incorporating students’ cultural capital that has been traditionally undervalued, the institutionalized inequities of higher education can be questioned and decentered.

By acknowledging the positive role of cultural capital in higher education for Black, Latino, Indigenous, poverty-affected, and first-generation students, Bourdieu’s three states of cultural capital potentially take on a new meaning:

- The embodied state can be thought of as the unique knowledge and experiences a student brings to the classroom that can be engaged to sustain their academic progress.

- The objectified state can be thought of as the material items with social significance to a student that can enhance their perspective and learning.

- The institutionalized state can be thought of as how the college or university perceives and engages a student’s cultural capital.

Cultural capital and digital learning

Digital learning affords opportunity to draw on students’ cultural capital. With innovations in adaptive learning software and digital multimodal compositions in higher education, courses in a variety of modalities can create spaces for students to explore their own cultural capital and hear from voices that reflect their own.

For example, multimodal composition can encourage collaboration. As collaboration occurs, students become engaged in discussion, building upon their cultural capital. This is taken further when collaboration is taken outside of the classroom, and community capital is built.

Discussion of cultural capital in higher education has long been confined to a deficits-based perspective. But as educators and academic institutions continue to seek ways to promote equity for every learner, the unique aspects that form students’ cultural capital are a resource to be celebrated and drawn on.

Download What Our Best College Instructors Do