When the authors of the latest edition of Tyton Partners’ Time for Class report looked at survey data that would inform it, one of the themes that emerged is that how faculty conceptualize the digital tools they use every day may limit what those tools do for students.

“Simply thinking of the LMS and courseware as containers and content will limit the potential for them to unlock higher-order thinking and more engagement for students,” says Catherine Shaw, Managing Director at Tyton.

Time for Class 2025 surveyed thousands of college students, faculty, and administrators about their experiences with digital learning. The annual report from Tyton Partners — the strategy, consulting, and investment banking firm focused on education — covers trends in usage of digital learning technology, student preferences for instructional formats, faculty support needs, and adoption of AI tools and analytics.

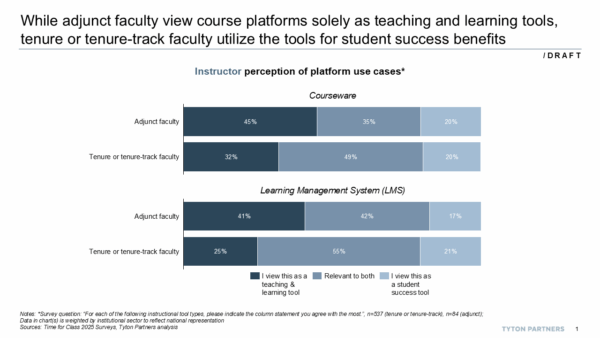

One insight is that many faculty take an instrumental rather than strategic view of digital learning platforms. For example, the survey asked faculty how they view their LMS and courseware platforms: as teaching tools, student success tools, or both. Most chose the first.

Shaw argues that this illuminates contrasting mindsets. One sees digital learning as an efficient way to distribute information, collect assignments, and record grades. And another sees digital learning tools as a creative way to foster student persistence, active learning, and engagement.

That’s an overlooked opportunity, she says: “If faculty were to think about LMS’s and courseware as student success tools and see themselves as agents of student success, that sets the stage for more.”

Rethinking what tools are for

For example, many LMS’s and other platforms today can support learning analytics, automate feedback loops, and scaffold learning experiences tailored to student progress. But most of that functionality remains unused while many instructors only engage with the platform as an administrative utility.

“All these digital tools throw off so much data we are just not capitalizing on,” Shaw says. “Part of it is faculty not spending time with the tools, but part of it is what institutions can do to support faculty in using the data.”

The mindset gap

What keeps faculty from taking fuller advantage of digital tools? Shaw believes it’s often a matter of framing. If instructors see digital platforms merely as delivery systems, they miss their potential as interactive learning environments.

That perspective may vary by faculty role. Shaw says adjuncts — typically hired solely to teach and rarely included in student support systems — may be more likely to see platforms as instructional aids. Faculty who advise students or interact with them in other contexts might be more inclined to see platforms as student success tools.

Shaw believes this points to an area with opportunity to improve digital learning. “Mindset and sentiment about the tools can really change the way faculty use them,” she says.

Examples of strategic use

Shaw points to peer-to-peer feedback in asynchronous courses as an example of a more strategic use of digital learning platforms. Peer review activities allow students not only to assess each other’s work but to reflect more deeply on their own development.

“It promotes higher-order thought and, even in an asynchronous setting, it can build community and engagement,” she says.

Another example involves embedding simple sentiment checks into courseware. After a problem set or quiz, students could be asked how confident they feel about their answers. That may help faculty identify individual students who perform poorly but report high confidence, which would suggest new opportunities to support struggling students.

Moving past the AI dabbling phase

While much of Time for Class 2025 focuses on courseware and LMS platforms, it also surveyed faculty about their use of AI tools. Those who use them regularly — especially daily — report much higher confidence that AI offers efficiencies in their teaching work, while faculty who are non-users or sporadic users are more likely to say AI doesn’t have value.

Shaw says the data comparing weekly and daily users of AI illuminates a “dabbling breakpoint.” Institutions should offer professional development that helps faculty move past that breakpoint and into purposeful integration.

“I didn’t really understand the value of generative AI until I pushed through the experimentation phase,” she says. “Now, for certain tasks, I’m 50/50 on whether I go to ChatGPT or Google. But that only happened after I built the muscle through regular use.”

The call to reframe

Faculty don’t need to overhaul their entire course design to start using tools more strategically. But they do need to shift how they think about what those tools are for.

“Faculty do this because they care that students learn,” Shaw says. “But the expectations for faculty time are crazy, and in particular as an adjunct you often don’t have the training or support to use these tools to their full potential.”

Still, she’s optimistic that small changes — adding a reflective prompt, using data to trigger outreach, inviting peer feedback — can all help move faculty toward a more strategic use of technology.

“Faculty are the primary point of contact for students,” she says. “If we expand how they think about the tools they use, we expand what’s possible for students, too.”

The full Time for Class 2025 report is available on the Tyton Partners website.